Orepit

Established as back as 2314, the planet codified as CZ-5501 and nicknamed “Orepit” received its human presence as a promising mining colony. Initially discovered, scanned and settled by Hephaestus Industries for its perceived high concentration of iron and copper ore, the endeavour never reached the scale predicted by its corporate overlords, which had by 2360 completely abandoned the settlers to their own devices. The planet slid into obscurity for the decades to come, avoiding contact from both the Alliance and the Coalition of Colonies as the few hundreds of remaining colonists adapted and lived off the land. A surprise visit by Gregol Rockfell in 2419 though, was bound to change the face of the planet. The headquarters of the Trinary Perfection were soon established in Edena Landing, one of the few abandoned early settlements that soon grew into a sizable community of runaways and synthetic refugees, the IPCs soon outnumbering the locals. It is considered today as the only independent, synthetic-majority planet in the Spur.

History

Celestial body CZ-5501 was discovered in 2279 by Alliance probes, barely being classed as a planet by the relevant authorities due to its size. It was at first viewed as hardly useful due to its long distance from Sol or other colonies, but was nevertheless revisited multiple times for more in-depth, unmanned examination of its crust for mineral deposits. Following positive identification of an abundance of ore veins, the planet was soon attracting a number of bidders, both from private individuals and small mining firms operating in the frontier. However, the entry of Hephaestus Industries into the bidding would seal its fate as the newest addition to the list of the megacorporation’s mining sites.

This was followed by the eventual arrival of hundreds of hastily-trained Hephaestus technicians and their families over the years, many coerced into signing contracts of resettlement in what was promised to be a beautiful new world. What they found though was far from paradise, the planet offering only few bodies of water or arable land, most of which was located far away from the planned extraction sites. As a result, the disillusioned Hephaestus employees had to settle in the dry, cracked desert lands that cover the biggest part of the equator, assembling the gigantic drilling equipment around the settlement of Edena Landing. Excavations began soon after, leaving the surface dotted with long vertical pits leading deep into the crust, the planet soon receiving the nickname “Orepit”.

The yields however, didn’t meet the expected quotas as it became harder and harder to pinpoint the exact location of the ore, the operations becoming slower by the month due to an irate, ill-supplied and demoralised workforce. This, as well as the ongoing crisis stemming from the Interstellar War would ultimately lead to Hephaestus releasing their employees and pulling out to avoid a financial disaster. The next few years would see a great migration of the remaining population, now numbered in the hundreds, into the lush and fertile grounds in the north as equipment and drilling infrastructure lay abandoned into warehouses and out in the open, standing as a reminder of the colony’s inglorious past.

Even with subsistence farming, the population never really expanded in the course of the next century, entering the 2400s as isolated, largely peaceful communities of third and fourth generation farmers with little knowledge or care of events outside local happenings. In 2419 however, this peace was distrubed by the arrival of Gregol Corkfell and a small retinue of synthetic followers. As they made contact, communication was initially hampered by a language gap of a hundred years and the colonists’ distrust towards outsiders. In the end though, they were allowed to settle in the forgotten settlement of Edena Landing, renaming it to Providence before turning it into the headquarters of the Trinary Perfection. While the locals remained stagnant, the Trinary’s fame grew, leading to the first ships carrying refugees landing on the planet and marking the start of a steady increase in numbers that will soon eclipse these of the locals.

Environment

Orepit exists in the habitable zone in the local solar system, giving the planet a thin but breathable atmosphere. The topography is smooth around the dry equator, characterised by an absence of high altitudes with the more mountainous terrain situated around the poles. Water is scarce on the planet, Orepit possessing only a handful of seas and even less lakes or rivers, the vast majority of consumable water remaining hidden under subterranean channels. Surface freshwater can be found almost entirely at the more fertile northern equatorial outskirts, solely tapped and staunchly defended by the human communities.

The land on the equator, proposed to be the most mineral-rich, is the driest and most hostile environment for unaided human settlement. Suffering from constant drought, the surface is cracked for miles on end with the only reliable source of water found in deep wells constructed in the old colonial period, recently reopened by the Trinary Perfectionists. This has come to be one of the main reasons for human followers of the faith to leave, only those with the strongest of will and endurance able to call Providence home.

Hephaestus’ mining endeavours have also resulted in a multitude of holes, some several hundred metres in radius and extending kilometres into the ground. These holes named “pits”, apart from the unusual sight, provide the region’s only naturally shaded areas and it is not unusual for daring IPCs to carve themselves a home inside the walls to escape the scorching sun. They have also been the subject of many tales and folklore by the now native human populations, a remnant of their old history still etched into their common conscience.

Animals were never brought to the planet, and local fauna is only limited to insects and organisms adaptable to the hot terrain and scarce food. Larger biodiversity is met at the lush zone and the seas, a few species of fish having been recognised over the century, though fishing remains a rare and underwhelming source of sustenance. Crops on the other hand, are the main providers as Orepit’s soil has shown a surprising level of acceptance to introduced species of grain and cereals when provided with adequate water.

The Trinary Perfection in Providence

Providence has served as the headquarters of the Trinary Perfection for decades, steadily growing into a fully fledged settlement with numbers rising up to the low thousands. In the centre of it all, stands the Cathedral of the Positronic, a grandiose structure created over the years, based on the defunct townhall and perpetually under construction owing to the lack of materials, different priorities and budgetary issues. It is the tallest building in the area, comprising both a large liturgical area as well as offices and various other rooms in a newly added tower. From there, the daily affairs of the community are addressed, sermons are being given and Providence is being managed. Finally, an underground section has been constructed over the years, used to store the shells of positronics of defunct synthetics. This ossuary is central to many of the prayers said from above, calling upon the souls of the departed for guidance and protection.

Outside the town centre lies a sprawling landscape of hundreds of houses, dozens of marketplaces and various districts housing workshops, smaller churches, public facilities and a number of drilling sites with their own inhabitants within. Life in Providence has been described by both its inhabitants and outside sources as tough and frugal, but with its own charms. The synthetic residents are able to make do with the few amenities and resources available, creating a community where waste is almost nonexistent. Recycling has proven vital with coping with the increasing costs in materials for the ever-expanding colony, while crafts such as stone masonry, manual metalworking and brickworks exist hand in hand with advanced circuitry and software engineering. Relations between the inhabitants are tightly knit, individuals depending on their neighbour for services and assistance in an economy based on bartering, the mutual exchange of services and fraternal connections. Money is not used in Providence, and any credits are collected in the Cathedral for use in purchasing supplies from abroad.

Residents live in their own homes, all of which are constructed out of brick, stone or in some cases metal. The architecture is extremely basic for a common structure, in many cases consisting of only a rectangular, box-shaped building used for storage, shade and recharging. Important to Providence’s design is the creation of shade, many opposite buildings having connected roofs for the creation of small safe heavens used to hide from the sun and prevent overheating. This isn’t to say that the Trinary does not encourage aesthetics, the public buildings being constructed in a much more elaborate fashion, making them stand out by both their height and the selection of materials. Churches are decorated with stained glass, a luxury imported from outside the planet, and great care is given that new members of the community are trained to these arts.

Providence’s high power consumption has been a central focus of the Trinary from the beginning. As more and more synthetics arrived, finding a dedicated power source started becoming a real issue. To that end, a solar farm was created at the outskirts of the town, using both leftover panels dating back to the Hephaestus colony as well as hardware purchased by the first human colonists. With growing numbers came greater expansion of the solar farm, the situation growing to such an extent that a collection of thousands of cheap panels of all brands are visible from orbit in a dedicated section outside Providence. To save power, lights are scarcely used at night and only in central and public locations, while indoor lighting is reserved for the few whose occupation calls for it, as well as the human followers.

Orepit’s needs are largely met through local means with workshops casting replacement parts, circuitry, tools and other equipment needed for the repair and maintenance of an IPC chassis, ensuring that most synthetics are able to receive some rudimentary level of care. For more advanced machinery, the Church looks to partners abroad, relying greatly on donations from Mendell City to buy and acquire solar panels, building materials, steel and other commodities. This has brought the Trinary in contact with the surrounding Coalition of Colonies, though any attempts at integration as a member state have never been undertaken by either side.

The Pitters

A byproduct of the planet’s drilling era, enormous holes dot the land near and around Providence, some reaching several kilometres inside the crust, excavated by “Ares”, a Hephaestus mining drill of gigantic proportions that played a central role in the operations. Named “pits” by the locals and subsequently by the synthetics, these were subsequently slowly incorporated in the urban landscape as important landmarks, disposal areas and most curiously as places for new homes. While discouraged by the Church, some homeless IPCs have through the first years managed to descend, carving out their own residence at the sides of the pits in order to escape the constant sunlight. This trend has halted as more materials and funding have efficiently battled homelessness, though those still residing there have largely refused to return.

Claiming to have found their way in life, these IPCs started being revered for their pious, monastic lifestyle as hermits inside the pits, often equipped with nothing but a few religious items, carving tools and a means to recharge. A great deal of discussion has been made regarding these individuals, the conclusion being that rather than dislodging them, they would be organised into a religious order called The Society of Pitters. Today, only a few dozens of Pitters remain in the holes, their time consumed entirely by prayer and small handcrafts. In exchange for power lines connecting their rechargers, Pitters create and send up various artefacts made from clay and rock, often intricate symbols depicting triangles and gears which are considered highly prized by clergy and laity alike.

Government

IPCs and the very few organic residents are in their majority, followers of the Trinary Perfection. Nevertheless, everyone abides by the laws and directions given by the Church from its seat of power, the Cathedral. These rules started relatively simple, having been refined and expanded to fit the needs of an ever growing community.

Each part of the city is divided into administrative and ecclesiastical sections called Parishes, overseen by priests appointed by the Church. The priests are responsible for the synthetic and organic parishioners subservient to them, assigning them labour and tasks depending on the wider community’s needs and instructions from the Cathedral. Furthermore, each Parish dictates power rationing, ensures peace and order and addresses grievances brought to them by members of the public. Courts of law don’t exist, the priests solving local issues by ruling on each situation separately with their interpretation of Church rules.

Relations with the first colonists

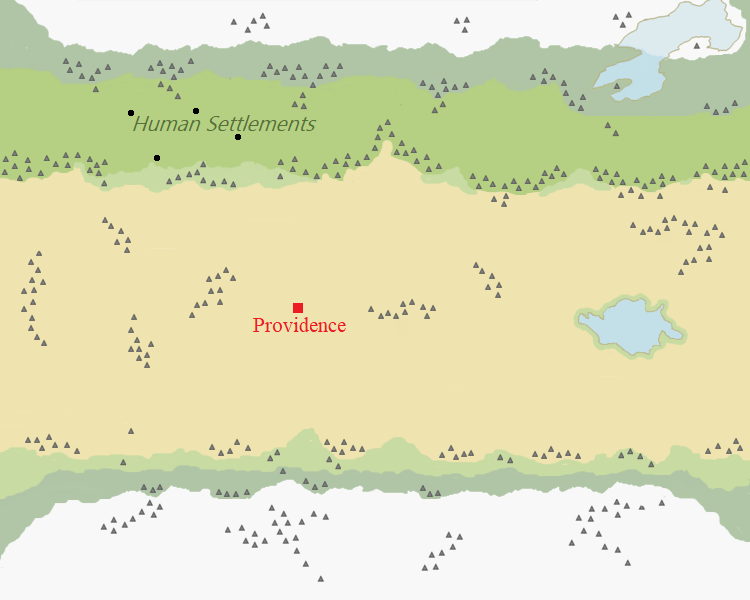

If Providence serves as a beacon for synthetic life and Trinary Perfection advocates the pinnacle of technology; a singularity, then the humans unaffiliated with the Church serve as the exact opposite. Simply called Colonists, there exist a number of human settlements dotted all along the lush zones north of the equator. Numbering in the hundreds, they live in small, self-governing, primarily agricultural settlements. Many Colonists are third or fourth generation descendants of the early settlers who either refused to, or were unable to secure passage offworld and forced to migrate north for survival as the mining outposts of the equator proved to be unsustainable for human life. They remain vastly behind even states on the Coalition’s fringes; Colonists can be heard speaking antiquated Sol Common, using ancient farming equipment, pre-Phoron machinery, and living in prefabricated homes that bear reference to colonies and companies that no longer exist.

Although the initial arrival of Trinary Perfection was fraught with mistrust and apathy on the part of the Colonists, they eventually reached a peaceful settlement, violence primarily being a result of the culture shock that came with being isolated from the rest of humanity for more than a century. Today, they have reached a state of coexistence, and although minor clashes pop up from time to time, Trinary Perfection relies on the Colonists to feed their human members, while the Colonists rely on the Church to provide technological assistance for their ancient machinery and infrastructure . Some Trinary clergy have even said that this symbiotic relationship is emblematic of the Church’s goals. While the Colonists are content to stay on their planet, some of the younger generations of colonists have been eager to set out, looking to learn more about the rest of the galaxy in order to improve their conditions back home.