Lyod

▶ This wiki page is currently behind the Phoron Scarcity update ◀

Information concerning phoron or the phoron scarcity may be outdated, lacking or unsatisfactory. Questions related to the phoron rework can be raised on Lore Discord.

The Lyod is the name shared in representation of the north and south polar ice caps that dominate the surface of Moroz, encapsulating roughly two-thirds of the total surface of the planet. These vast regions are primarily composed of arctic tundras in which very little grows and few animals reside, though they are not completely devoid of life. Dense taiga-like forests composed of Morozi conifers and larches can be found in the regions of the Lyod bordering Equatorial Moroz, and the majority of the Lyod's population can be found in and around these forests during the colder seasons. The taiga of the Lyod has been home to Dominian outposts for several decades now, which has brought the Empire into contact - and conflict - with the native population of the region: the Lyodii (the "People of the Lyod," in Vulgar Morozi).

Names of Lyodic peoples could fall in line with the traditional names of Asiatic indigenous peoples in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Earth, such as the Inuit, the indigenous peoples of Siberia (Sakha, Buryat, Kamchatka, Altay, Khanty-Mansi, etc.), Karelia and Sápmi, as well as the Ainu people of Japan and eastern Russia.

History

Despite its formal establishment in 2137 the settlement that came to be known as Nova Luxembourg did not formalize any observations or study of the Lyod or the Lyodii until the early 2300s, when migrations of large groups of people were spotted during routine flights between the future capital of Dominia and the Holy Kingdom of Domelkos, often taking routes around the north and south ends of the Fisanduhian Range. With the premise of war on the horizon with the Confederated States of Fisanduh these nomadic masses of humanity were largely ignored until Fisanduh’s collapse in the late 2300s as reports of looting were becoming increasingly common near battle sites surrounding the Range.

Chance encounters with the scavengers by Dominian scouts in the 2390s slowly began to put together an image of loosely-organized tribes of up to several thousand surrounding the taiga forests that formed the boundaries to Equatorial Moroz, often just within reasonable traveling distance of outermost battle sites but just distant enough for aerial forces to pass by them undisturbed. As these interactions became more commonplace among reconnaissance units the fledgling Empire began to cross-reference records from the initial colonization period to names learned from primitive signage and discovered that the wary wanderers had descended from multiple lineages of exiles, criminals and agitators that survived ostracization from society proper. Over the next several decades leading up to the current day the Empire would establish outposts on the border of the Lyod, enticing both opportunities for trade and conflict as they looked to both study - and tame - the Lyodii and their unforgiving home.

Environment

Both the Northern and Southern Lyod are predominantly covered in taiga, boreal forests consisting of coniferous trees of various species, closest to Equatorial Moroz. Moving further north or south the landscape transforms into harsh tundra, and the capacity for soil to sustain plant life diminishes considerably due to lack of moisture and nutrients. While Lyodii have been recorded to visit the Northern cap for spiritual practices the Southern cap is rarely traversed due to the hostility of the cold.

While both Lyod are considered inhospitable to the average Dominian, the Southern Lyod has been consistently recorded reaching temperatures far exceeding the Northern Lyod, going as low as -75 Celsius (-103 Fahrenheit) during winter due to the presence of an enormous ice sheet beneath most of its surface. For this reason a majority of Lyodii living in the Southern Lyod are seldom seen beyond the taiga and mountains at the border to Equatorial Moroz, as most of the ice sheet’s landmass is completely devoid of life.

The Northern Lyod, with much more hospitable winters hovering at -50 Celsius (-58 Fahrenheit) and summers cresting around 5 Celsius (41 Fahrenheit), is considerably more populated across its surface with a bulk of its observed population surrounding the only body of water in either Lyod - the Lyodic Sea. Temperatures along the Lyodic Coast tend to hover several degrees higher than elsewhere in the Northern Lyod, lending to semi-permanent settlements that enjoy a sustainable amount of commerce year round.

Locations of Interest

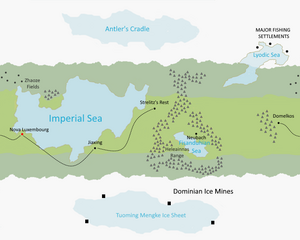

- Lyodic Sea: The only body of water in either the Northern or Southern Lyod, the Lyodic Sea hosts the majority of Lyodii semi-permanent settlements in the Northern Lyod due to the more temperate weather conditions promoted by its size. The Lyodic Coast enjoys a consistent barter economy year round centered around trade of cattle and fish retrieved from the sea. While fisherpeople in the southern coast of the Lyodic Sea see regular trade with Domelkos due to the unique flavor profile of Lyodic fish, most further north trade only with each other in order to keep Dominian influence at bay. To the Lyodii this body of water is known as ‘Old Dolgun’, referring to an apocryphal tale of a water spirit known to dwell within the sea that taught the first Lyodii to fish.

- Cairn of Caladius: The Cairn of Caladius represents a vast swath of rolling tundra hills broken up by fragmented ice and lakes in the uppermost center of the Northern Lyod. Its namesake derives from the plighted missionary journey of Iuliana Caladius, a High Priestess of the Tribunal whose caravan came into hostile contact with an aggressive tribe of Lyodii in 2410. After several weeks of silence from the party the Empire dispatched an Imperial platoon to scour the Cairn for survivors, finding only bloodied clothes and broken weaponry. To the Northern Lyodii this stretch of tundra is known as the ‘the Cradle’, short for ‘the Cradle of Antlers’ - the place of destiny in which the Lyodii first tamed tenelote and reindeer.

- Tuoming Mengke Ice Sheet: The Tuoming Mengke Ice Sheet is a vast body of impenetrable ice that makes up a majority of the Southern Lyod, and is the primary cause of its inhospitable cold. While the icy plain is devoid of life and scarcely traveled by the Southern Lyodii the wealth of rutile, ilmenite and zircon in the sediment beneath its surface have made its geographical border a hotspot for Dominian mining operations. The Southern Lyodii take care to avoid it when able and often colloquially refer to it as “the Barrows” in the belief that a malevolent spirit is imprisoned beneath the ice, and that the Empire threatens to release it.

- The Heleainnás: The Heleainnás is the unofficial name to the southernmost series of mountains in the Fisanduhian Range that tightly hug the icy clutches of the Southern Lyod, infamous for its treacherous topography that made flying a nightmare for Imperial pilots during the Morozi War. Its namesake derives from a supposed carving at the summit of its highest peak, Mount Khankai, of the name “Heleainná” in Lyodic Morozi script. The Southern Lyodii have learned to call its myriad of valleys and montane forests home, and routinely engage in trade with those Fisanduhians who still remain in the region.

- Zhaoze Fields: The Zhaoze Fields are a vast muskeg stretching through a significant portion of the Northern Lyod’s border taiga. They are widely regarded as a ‘place of death’ by the Northern Lyodii, and seldom visit it as they believe it harbors the hostile spirits of deceased Imperials who have sunk into the peat. The Empire avoids it from a tactical perspective as it poses a significant geographical border to the tundra plains north of it, and many men and vehicles have been lost to its treacherous terrain.

Flora and Fauna

Due to the vastly different conditions of the Northern and Southern Lyod in comparison to Equatorial Moroz the flora and fauna present in both poles have uniquely adapted to its hostility, spawning regional variants to its known species as well as ones entirely unique to their icy biomes.

- Lyodic Tenelote: While the equatorial tenelote have long been used as pack and riding animals, the Lyodic tenelote are treated as cattle by native herding clans - their compact physique, hardy skin and thicker coats providing a consistent source of meat, leather and fur. They are easily differentiated from their equatorial relatives by their grey to white coats and shorter appendages.

- Lyodic Prejoroub: Perhaps the most well-known of Morozi fauna due to their likeness being used on Imperial naval vessels the prejoroub of Moroz are known to be cunning and fierce predators, and their Lyodic counterparts are perhaps even moreso. Growing considerably larger than their equatorial cousins and sporting a coat that changes color with the season, the Lyodic prejoroub have long been a menace to Lyodii herding clans and often take to preying on wandering cattle when food is scarce.

- Lyodic Yastr: Though the range of Morozi yastr are effectively contained to the Fisanduhian Range, a unique branch to this bird of prey have spawned in the Heleainnás, where the mountains sit closest to the Southern Lyod - the Lyodic Yastr. While not as quiet or tameable as their traditional cousins they sport two coats of feathers for cold weather flying, and are known to roost considerably higher in the mountains for this reason. Due to the diurnal nature of this subspecies, in contrast to their nocturnal relatives, Southern Lyodii believe that seeing an equatorial yastr fly overnight as an ill omen.

- Bisumoi: The bisumoi is an enormous, moose-like herbivore most recognizable for its two sets of antlers, brown and grey mottled coat, and three sets of long unguligrade legs. While mother and calf bisumoi are known to travel in groups with other females rearing young to protect offspring, males are solitary and are known to walk hundreds of miles – utilizing the locomotive power of six legs – to find a mate regardless of season. Both males and females grow two sets of antlers, with males growing such large racks that they often intertwine and are mistaken for tree branches at a distance. They are one of the few animals on Moroz that prejoroub are known to avoid in packs of less than six, their tough hides and dense layers of fur posing as excellent defenses to claw and tooth. On rare occasions white bisumoi have been spotted, and are known to be a sign of winter approaching by both Northern and Southern Lyodii.

- Boreal Ptarmigan: One of the lesser known bird species of Moroz due to its exclusion to the Lyod, the boreal ptarmigan is a medium-sized game bird between the treutduro and yastr in size. Its unique blue-white plumage and excellent taste have made it both a target for Lyodii clans looking to diversify their diet and Dominian game hunters who dare to travel the Lyod for sport - often with mixed results. Northern Lyodii have been recorded mimicking its mating call to better attract a potential meal - and on some occasions lure ignorant hunting parties to an ambush.

As with some other human-colonized worlds, a number of Solarian flora and fauna well-equipped to colder climates have flourished across the surface of Moroz: reindeer, arctic fox, hares, muskoxen, mountain goats, and various arctic and subarctic flora are all commonly sighted across the planet. Whether by diaspora during the initial colonization years or by artificial introduction following the Empire’s opening to the Spur these animals are no more out of place than the native species, and have found themselves carefully protected by both Dominian conservation laws and passive Lyodii caretaking.

The Lyodii

Due to the harsh and often life-threatening conditions of living in the icy poles the Lyodii have learned to survive and thrive on its land through traditional means (animal husbandry, subsistence farming, fishery) and the unconventional adaptation of technologies abandoned by the Empire. This has made the Lyodii renowned across Moroz and Mira Sancta for being not only hard-working, dutiful and clever laborers but also staunch companions and adversaries.

Society

Though the Lyod is home to some small permanent villages that are generally located in the more hospitable taiga zones as well as the coasts of the Lyodic Sea, most Lyodii live in small nomadic communities of anywhere from several hundred to several thousand members that follow cattle herds and plant growths around the tundra. These Lyodic tribes follow no authority beyond an appointed chieftain or council and the clan shamaness, who may additionally serve as the clan’s chieftain in circumstances where a chieftain is not an appointed role in a clan. The responsibilities that entail a clan’s survival are distributed from the chieftain, council or shamaness to the leaders of each family in the clan, ensuring that all members of the clan participate in its success and instilling a strong belief of mutual aid and community into each member. While conflict is not uncommon between clans – particularly when resources are scarce – most tend to avoid conflict with one another on principle, as their lives on the tundra are challenging enough without warring over hunting rights, grazing territory, and cattle disputes. For this reason, in contrast to Imperial customs, honor dueling is universally frowned upon and seen as a waste of resources and the potential for peaceful reconciliation. Clans, however, have been known to unify into larger confederations in response to external threats such as Dominian efforts to "tame" the taiga and tundra of the Lyod – and have been known to shun those Lyodii who have volunteered their time and survival skills to the Empire, either as advisors to Imperial expedition groups or as members of the reviled Lyodic Rifles.

Daily life for the Lyodii revolves around the difficult task of ensuring that they, and their clan, are able to continue surviving in the Lyod, where they can be free from the Mo'ri'zal and the influence of the Empire of Dominia. To fail in one's tasks runs a risk not only to one's own life but to that of the entire clan, and failure or refusal to perform is typically met with harsh punishment by one's parents, the tribe's more senior members, or potentially exile if an offense is severe enough. The nature of life for most Lyodii means that one is almost always on the move following animals or plant life, and many Lyodii that travel off-world are often used to (or uncomfortable with) staying in one spot for only months at a time. This nomadic lifestyle is not present in the rare villages that dot the taiga and the Lyodic Sea coast, which often serve as meeting points for inter-clan diplomacy and trade centers where the resources of the Lyod are exchanged between clans. These villages are additionally some of the few opportunities Lyodii have to go off-world, as they are the only places where those with the funds needed and interest to recruit Lyodii for megacorporations -- primarily Zavodskoi Interstellar -- can be found.

Culture

The myriad of backgrounds of those exiles and outcasts that eventually evolved into the Lyodii have led to the formation of a syncretic culture entirely unique to the Lyod, unified under a universal belief in community borne of decades of struggle against the Empire and the elements. Extreme mortality rates among youths and lower than average life expectancy among adults paint a grim reality that have not only hardened the collective consciousness of the Lyodii people, but encouraged an unwavering culture of everyday intimacy that most non-Lyodii may find themselves ill-equipped to understand. Emotional honesty, responsibility to others and the will to self-sacrifice are not only seen as values paramount to the survival of one's tribe or clan, but the ideals that all Lyodii should strive toward as the ultimate expressions of love and compassion. Daily activities and responsibilities among families and tribes are virtually always performed in pairs or groups, making what could be potentially tedious or dreary tasks opportunities for sharing company and conversation while also being beneficial to general safety. Disagreements and conflict are often settled in view of a third party who behaves as both mediator and mutual friend by reminding opposing parties of shared values and feelings to further close the gap. When such tensions cannot be resolved by said party, the third party will take the matter to a tribe elder who will require the opposing parties to engage in discussion in view of tribe members of repute until both have exhausted the matter or reached reconciliation. Matters of romance and marriage are unilaterally left to the devices of courting persons, with the concept of courting into status in a tribe being viewed as extremely taboo. Matrimonial ceremonies are often conducted by a tribe’s priestess, and are celebrated for days to weeks by associated families. While these unions may be officiated and blessed by a tribe’s holy person they are not spiritually binding, and can be renounced at any time by either party privy to it.

While attempts have been made in recent years by many tribes to improve on basic education among youths, literacy and numeracy are sharply below average for Lyodii when compared to their Imperial Morozi counterparts. The lack of centralized institutions and unreliable sources for reading and writing material have made even basic literacy uncommon, often to the detriment of those Lyodii who live nearest to the Empire and engage in trade at border outposts. In reaction to this deficit, through generational adaptation and cultural practice, music and the spoken word have taken a critically prominent role in Lyodii community affairs. Stories of yore and cautionary tales are often told with theatrical zeal and may be accompanied by music or costume, usually sewn by the family of the performer. Song and singing hold utilitarian and cultural value, used for both ritual and signaling cattle and company when traditional means may fail at considerable distances. A tribe or clan’s luthier or instrument maker are particularly respected persons, often taking place among a tribe or clan’s elders due to the years of practice required to make finely-tuned instruments. With such emphasis on expression through lyrical and instrumental means it is common for any one family to have several members who learn to sing, dance or play an instrument at an early age and continue to do so throughout their lives. Such practices are often considered bad omens to Imperial foot soldiers traveling the Lyod, with Lyodii songs and instruments being heard and recorded by Dominian outposts and caravans from up to several kilometers away. While largely ignored by Morozi society at large, these expressions of the Lyodii spirit are known by those Dominians and Fisanduhians who inhabit the border territories to hold an eerie and ageless beauty.

Perhaps the most obvious and distinguishing feature of the Lyodii when compared to their Imperial counterparts is the unique blend of utility and tradition that informs their fashion - or lack thereof, depending on who in the Empire one may be speaking to. Furs, leathers and other natural products fulfill the primary roles of protection and insulation in clothing where synthetic materials are traditionally dominant but are otherwise scarce in the Lyod, with clothing sewn with home sewing machines where available or by hand by one’s self or a family member. Clothing left abandoned by Imperial caravans or traded for at outposts are frequently modified to suit the needs of its wearers, meshing synthetic fabrics and Imperial designs with natural and traditional Lyodii ones, creating something that is both neither and yet distinctly Lyodii in execution. Jewelry is universally derived from natural sources (antler, bone, wood, precious gems) as it is considered closest to the body, with all Lyodii regardless of gender wearing it on a casual basis. Tattoos are considered an especially sacred practice by those tribes who may historically wear them, with some using modern technologies for their implementation and some using more antiquated methods to preserve wholeness. Emphasis on certain colors, patterns or designs may form the unique profile of any one tribe, with such factors denoting one as a member of said tribe to other Lyodii and expediting the process of determining friend or foe. Such features also make Lyodii impossible to miss in Dominian society, and often the focus of tokenizing attitudes and exoticism.

Religion

Having separated from what would become the Empire generations before its establishment of dominion over Moroz, the Lyodii follow a unique and aberrant interpretation of Goddess belief colloquially known in Mira Sancta as Lyodic Paganism. Though each tribe’s beliefs tend to vary on a regional basis, incorporating different themes often deriving from the backgrounds of their ancestors, one universal and unique trait of this brand of Goddess worship can be found regardless of location: animism, or the belief that objects, places, and living things all possess a distinct spiritual essence. In this dynamic the Goddess is less an explicit deity but more an all-encompassing presence that permeates all things in the universe, granting a distinct and immutable grace to places, objects and beings that otherwise may not be seen to have such by the average Tribunalist. A profound reverence for nature, a strong respect for autonomy and unwavering dedication to one’s community are foundational to Lyodic spiritual doctrine, represented in the myriad of different rituals and social activities of tribes in both poles. Examples of these practices could be:

- Giving an animal hunted for sport or sustenance a proper and respectful burial rite and prayer prior to being parted for bones, fur and meat - nothing is wasted as a means of showing respect for a successful bounty

- Performing elaborate and respectful rituals for animals who are mercy killed due to illness or injury, or for sacrifice in offering to the Goddess - as with game, nothing of the animal is wasted and anything not used is left to the wilderness for nature to reclaim

- Coming of age rituals and celebrations for teenage and adult Lyodii as both a means to test the mettle of tribe members and also to thank the Goddess for permitting them to survive into adulthood

- Prolonged and openly displayed behaviors of mourning for clan members who have passed, often continuing for days to weeks to months at a time depending on the age of said member and the clan’s practices

While spiritual practices vary from region to region in either Lyod, a particularly unique perspective of the afterlife has been known to be propagated among those Lyodii living within the montane forests of the Heleainnas, taking after their precipitous home. In this depiction the path to the afterlife and the Goddess’ eternal embrace is an enormous mountain made of glass, posing as a literal and figurative obstacle to which the spirit must both climb their way to the summit and also reflect on actions taken during life. As the path to the summit is considered difficult even for the most seasoned climbers, Lyodii often bury their deceased loved ones with food and equipment to better aid them on their journey beyond.

Conflict with the Empire

The relationship between the "letterpeople" (Lyodic term for Imperials, often bearing documents of some official legislation) and the Lyodii remains virtually unchanged from their colonial origins, aspirations of empire and the fate of exile profoundly orchestral to the foundation of the Lyodic way of life. As the dominant entities of Moroz the Empire and by extension the Tribunal pose an existential threat to the Lyodii people, an often distant but terminal presence to which the Lyodic cultural consciousness remains ever vigilant. The existence of their society on Moroz represents a defiant, untamed identity that mars the face of cultural, spiritual and societal oneness to which the Emperor and the Tribunal strive to unite the Imperial homeworld, only controllable to the extent of those few who choose to leave the Lyod and the Empire's control of the historical narrative as the premier power of Mira Sancta.

Despite these generational tensions open hostilities are seldom seen, the Empire often reluctant to spare resources to fund ventures to either Lyod where failure is a likely outcome. Inclement weather, lack of logistics infrastructure and nearly universal disdain from the native population mean certain disaster for anything but the most conservative operations, with successes often short-lived or offering weak results. Indirect means to undermine the Lyodic identity have taken precedence in recent years for this reason, the efficacy of such operations most obvious among the tribes and clans closest to Equatorial Moroz. Promises of material gain, protection from other tribes and the allure of citizenship are used to sway those tribes who find themselves struggling or without tribal alliances, often sending those few able individuals among their numbers to the Lyodic Rifles as a means to prove loyalty. The equatorial tribes who refuse these offers often live embattled lives, their societies and organization often more cutthroat and brutal than those further from the Empire. The constant threat of violence from Imperial expeditionary units and turncoat Lyodic tribes have reduced these tribes in both Lyod to few in number, and in recent years many have found themselves moving further north or south to avoid extinction.

For those Lyodii who leave the Lyod for the Empire, life often changes little despite the reluctant acceptance of its authority, many facing difficulties previously not experienced while at home. Lyodii seeking education and opportunities outside of Moroz or Mira Sancta are often pressed into lengthy, predatory contracts with Zavodskoi in order to finance tuition and healthcare costs, often spending eight to twelve years minimum working for the megacorporation before being afforded basic amenities the average Dominian employee may enjoy. Long hours at dangerous worksites, either off-world among the many Imperial subjects or at any of the myriad locations on Moroz, are a routine endeavor for most Zavodskoi Lyodii employees. Retention rates are generally mixed, with those tribes at the equator most acclimated to Imperial presence and enjoying a more comfortable transition than their more northern or southern cousins. Most severe to Lyodii choosing to integrate into Dominian society is the reluctant acceptance of the mo'ri'zal, both as a financial and social obligation. As a majority of Lyodii remain undocumented by the Imperial government, recording and tracking blood debts is considered a lost cause until one chooses to find official employment or citizenship in the Empire proper. The mo'ri'zal and its sociocultural connotations often push Lyodii living in the Empire to live private and conservative lives, their status as an underprivileged people even by ma'zal standards often leading to a quality of living which falls below the average Morozi Dominian. Discrimination of Lyodii is a fairly commonplace practice among the Morozi gentry who predominantly make up the functionary bodies of educational institutions and Zavodskoi facilities, with ma'zals and lower class laborers finding themselves anywhere from ambivalent to familiar with those Lyodii they find themselves toiling with.

Conflict Within

Despite unspoken cultural agreements between Lyodii tribes to avoid conflict the Lyod does not remain without its own internal strife. Particularly brutal winters, dry springs and cattle diseases can aggravate trade agreements between tribes, sometimes to the point of violence if one or both tribes are significantly harmed by the lack of food. Debates on grazing territories for cattle, coastal grounds for fishing on the Lyodic Sea and lumber rights in the taiga occasionally come to blows, often leading to brief but intense skirmishes until one tribe either capitulates or an attempt at reconciliation is made by opposing shamanesses.

Most notably among quarrels is the severe disdain among many Lyodii for Imperial sympathizers, particularly those employed by the Lyodic Rifles. While leaving for the Empire to seek education or work is often seen as an unfortunate but necessary task, cooperating with Imperial military officials operating in the Lyod or joining the Lyodic Rifles is often seen as an irremovable black mark upon the reputation of any Lyodii. While Imperial collaborators, much like the few raiders and thieves that spawn from hardship in the Lyod, may be afforded their lives if captured by being formally exiled from Lyodii society, Lyodic Rifles are seldom spared from summary execution or worse. To use one's skills and experience, inherited from one's kin and elders to survive the Lyod, against their own in service of the Empire is considered an irreconcilable offense that can only be equalized in death. On the rare occasions a Rifle is captured and spared from execution, often after considerable deliberation between authorities in one's former tribe, a Rifle may be branded "spirit-blinded". In this practice a Rifle may have a Tribunal eye, depicted shut, forcibly tattooed in black ink on their forehead - a visible depiction of their total ignorance of the Goddess' intentions for the Lyodic people, and a warning sign for those Lyodii who may encounter them.

Lyodii Beyond Dominia

If Lyodii in the Empire are a sparse sight, Lyodii beyond its borders are an even more extreme rarity. Work visas come with incredible difficulty, the Empire’s organs of immigration upholding an unspoken reluctance to granting visas to its less than loyal citizens. Many Lyodii who are lucky enough to acquire one find themselves working in positions elsewhere in Mira Sancta before being granted permission by their primary employer in the Empire, Zavodskoi Interstellar, as a test of loyalty before being offered transfer out of system. While fields of expertise tend to vary among Lyodii depending on the investment made into their skills by their benefactors in Zavodskoi, many often find themselves in low key security and engineering work as they are often the shortest paths to gainful employment elsewhere.

Those Lyodii who go above and beyond, both in displays of aptitude and loyalty to the Empire, are often considered for advanced education in the sciences and medicine and pressed into sometimes life-long contracts that draw serious penalties for failure to perform. Zavodskoi take great care to make these select few obvious in their facilities and elsewhere in an attempt to showcase their “concern” for the Lyodii people, often to the detriment of the individuals themselves as they quickly become the focus of ire of both the average Morozi Dominian and their fellow Lyodii in the workplace. Despite this retention for these individuals remains high as the quality of living is considered leagues above the average Lyodii’s, and can be said to offset the punishment of being considered a turncoat by one’s tribe.

Even rarer than Lyodii working abroad are Lyodii expatriates, those who choose to permanently settle elsewhere in human space. While the Empire’s official stance on Lyodii expatriation remains largely ambiguous, expatriation often finds itself a nearly-impossible task by those bound by long-term contracts with Zavodskoi, often able to hamstring the opportunity for employment required by most human systems to settle on a work visa. Such matters, if accomplished through official channels, often take months to years to plan and organize and often to the tune of a hefty “tax” debited at the time of signing. While dual citizenship with certain polities are largely permitted, those Lyodii who carry citizenship with the Coalition of Colonies are often held to a higher standard of scrutiny, and are far more unlikely to return home if at all.